By Yaling Jiang

“Dior’s Haute Couture isn’t as inaccessible as you thought,” a Little Red Book user, currently in her PhD program in California, shared earlier this year about her made-to-order experience with the brand in Paris. “You used to have to have to fly to Paris at least three times from the first to final fitting, but now the brand sends their team of dressmakers and seamstresses to Beijing and Shanghai to do the fitting for you.”

The world of haute couture, where individual pieces of high-end fashion are crafted by hand from start to finish, has only become more accessible to Chinese consumers lately. “When luxury started, it was all made-to-order,” said Janice Wang, CEO of the global fashion tech company Alvanon, referring to the exclusive tailoring by a team of highly crafted seamstresses and makers behind European luxury houses. However, once largely associated with haute couture, made-to-order now also refers to a whole new world of technologically dependent customization services, from Nike sneakers to luxury handbags to personalized items on clothing, all of which have made their way to China in recent years.

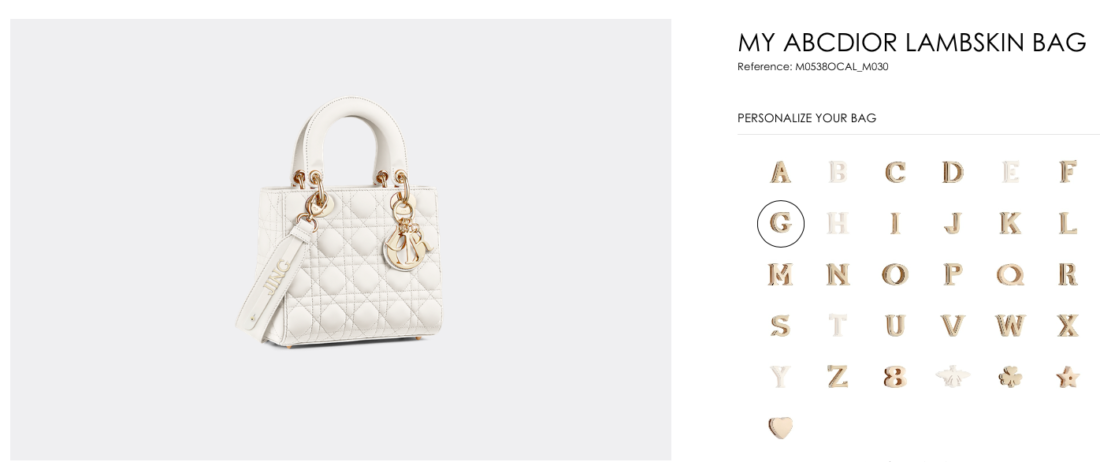

This new type of made-to-order appeals to Chinese luxury consumers, as a growing number of them want to stand out from the crowd. In a March report, McKinsey pointed out that for Asia’s millennials and Gen-Z consumers, customization is no longer a nice-to-have option but “an expectation,” which might explain the ubiquitous services from Dior’s own My ABCDior and Louis Vuitton’s My LV Heritage that offer light customization on luxury items.

But as one’s consumption power goes up, their expectations for the range of options graduate from light customization to full bespoke services, or even customization beyond what brands offer. Customization within the brand is increasingly valued by high-net-worth-individuals, which are luxury goods’ core customers, said Dr. Zhou Ting, head of research at Shanghai-based Yaok Institute, which has surveyed more than 40,000 China’s millionaires and billionaires (in local currency). “They want to present their personality and their standard for quality; the trend is even more apparent when it comes to China’s billionaires, who want customization above the brand,” she said.

Outside of China, some luxury brands’ made-to-order initiatives have shuttered. Burberry Bespoke, an initiative that was launched in 2011 for its iconic trench coat was quietly folded in 2015. The British brand offered light customization for trench coats in the London flagship before it was shut due to the coronavirus. And even before the COVID-19 pandemic took over the world, Jimmy Choo’s made-to-order service has been “temporarily paused”, according to its US and UK website.

While made-to-order has seen mixed results in global markets, China’s vast market is ready. From young consumers to high-net-worth-individuals, shoppers’ increasing expectation presents an opportunity for brands to expand services, and moreover, to adopt the made-to-order mindset for their future with the help of technology.

Back End Help: How Tech Can Lend a Hand from Communication to Fitting

While the luxury world rolls out different levels of customization services, fashion tech entrepreneurs envision a world where the made-to-order functionality could be adopted to back end operations. Co-founder of PlatformE, the start-up that powered ABCDior, is one of them. “The inventory system, which underlines a forecast model [in which the future order is decided based on historical data], is now recognized as dysfunctional, because you are most likely above your forecast,” said Ben Demiri. Overproduction and deadstock, or the merchandise left unsold, are what contributes to fashion’s waste problem, he added.

While fashion retailers usually discount part of the deadstock, the luxury industry frowns upon this system as it dilutes the luxury brands’ value and exclusivity. For brands and retailers, however, deadstock is a financial burden. But the real issue arises when deadstock ends up in landfills or worse — burnt. The old industry secret was brought to light by Burberry’s burning of $37 million worth of unsold bags, clothes, and cosmetics in late 2018, which backfired greatly for the brand.

Made-to-order can also be the solution to the currently linear supply chain model, which isn’t agile to the fast-changing demand, Alvanon’s CEO Wang said. “The rise of digital media only magnifies the issue,” said Wang. “The mismatch right now is that a digital consumer is being served by an analog supply chain.”

Unlike direct-to-consumer brands that were born in the digital era, the “analog supply chain” that Wang described were built and used by luxury brands in the last few decades, which is hard to shift overnight. As a process that glues suppliers, production, distribution, and customers, it’s usually connected with emails, calls, and spreadsheets to pass information from one link to another. Both Wang and Demiri believed that it could be more efficient with technological advancement.

Back in 2015, when Demiri partnered with co-founders Gonçalo Cruz and Farfetch‘s Jose Neves to create a new sneaker brand, but discovered, instead, the need for a just-in-time production process for the whole industry. And PlatformE offers software suites for brands to manage made-to-order production and orders to make it more agile. It has attracted investment including The Amorim Group, The Luxury Fund Management and Carmen Busquets, luxury e-tailer Net-a-Porter’s first investor.

From a back-end perspective, the company transformed the linear supply chain model to an interconnected one, so that when a customer puts in a personalization request at the front end, the brand would automatically receive instructions for production, which then enters its supply chain.

“We use a platform approach that enables a one-to-many-type of communication, which is pivotal when it comes to scaling made-to-order,” Demiri said, adding that while traditional made-to-order is highly manual, there is a need to standardize the order information in between the brand, its manufacturer, and retailers. So far, the company has worked with Gucci, Dior, Nicholas Kirkwood, Nordstrom, and Farfetch.

During the same period of time, however, the customer doesn’t want to wait in the dark. “The most exciting part is that the customer can track their item in real time,” Demiri says. “Brands can upload photos of the product being made and customers can learn about the craftsmanship and share these images [on social media].”

While PlatformE’s platform supports the interconnected communications within the supply chain, Alvanon’s technologies can fasten the process of a brand’s product development as much as eight weeks per season, its website says.

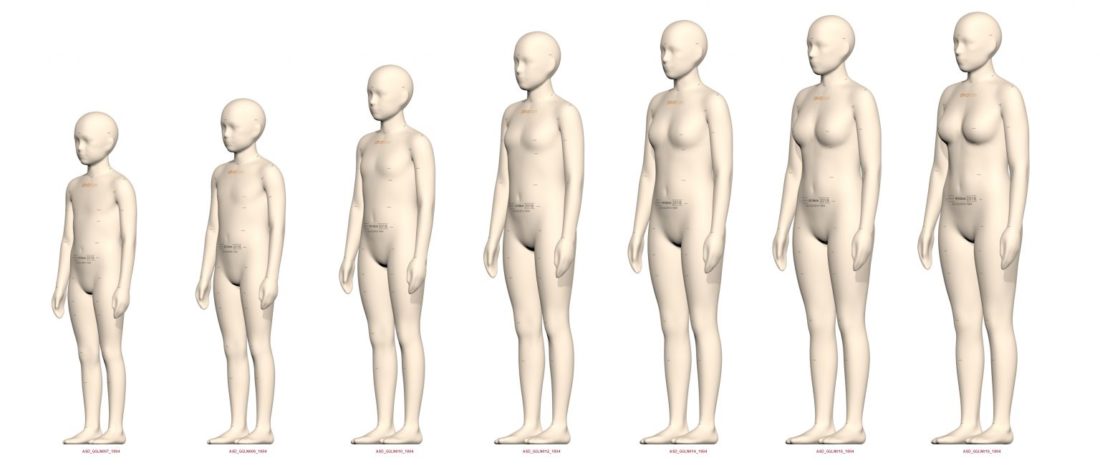

The company helps brands — Chanel, Alexander Wang, and Coach, to name a few — establish each of their own sizing schemes with its 3D scanning and data analytics technology. As a result, the legacy design process can be shifted to a 3D virtual sample creation, development and approval. “3D is the first step on the road to mass customization,” CEO Wang says. “Clients who have been working with the 3D avatars are able to make much better products. They have also been able to move faster and increase speed-to-market to remain competitive.”

While technology like 3D would ease up the scaling process for brands’ made-to-order offerings, it might be able to change customers’ experiences in the future. “You used to go to the tailor and they would make one item for you. I can visualize that one day you will customize bespoke, customized, perfectly fitting items made just for you, just like a Savile Row offering, only this time it will be purchased from your smartphone,” Wang says.

Front End Needs: Unresolved Issues and Opportunities in China

The demand for made-to-order, mostly light customization, is sprouting on China’s social media. Among the sea of brands’ offerings their own customization, there are also unofficial sellers that offer to add a personal touch to people’s luxury items with classic patterns, like Louis Vuitton’s Monogram and Goyard Chevron. On Little Red Book, the 4,000 posts under the tag “made-to-order luxury” are mostly ads from customization shops that take orders to draw anything on one’s luxury item from cartoon figures, to pets, and their loved ones.

And from the increasingly positive social reactions, consumers want customization services from luxury brands, and when they don’t offer these services, they’re exploring other routes to meet those needs. However, some brands are waking up to this and beginning to explore options more intently.

Gucci, for example, is expanding its customization offerings categorically and geographically. Upon launching customization services in Beijing’s SKP flagship store in 2016 for handbags, Gucci is also offering made-to-order menswear services in tier-one cities like Beijing and Shanghai, as well as in tier-two cities like Shenyang and Chengdu, Yaok Institute’s Dr. Zhou said. A regular Dior customer from Jiangsu Province also told Jing Daily that the brand has invited her to a few private customization handbag events in Shanghai.

To Dr. Zhou, the majority of the light customization is not a real made-to-order item. “We call this ‘fake customization’ because a customer’s choices are restricted,” Dr. Zhou said. There are different types made-to-order for customers: one is the customization “under the brand,” which aligns with the public perception of made-to-order luxury. The second type is “above the brand,” meaning that the customers still want something specific from the brand that’s outside its current offerings. The highest level is free customization, for example, when someone “may want the Hermès to design an outfit with Zegna’s materials,” Dr. Zhou says.

What used to be an additional service for luxury brands has grown with the Chinese market. Some brands’ made-to-order services have become a driving force for their China area’s double-digit growth. For others, made-to-order accounts for as much as 70% of the companies’ sales, according to Yaok’s research.

Along with made-to-order expansion in China, issues have surfaced. “Chinese people have different body types compared to Europeans, so when European luxury brands use their sampling for Chinese customers, it doesn’t fit,” Dr. Zhou says, adding that one loyal Hermès customer told Yaok Institute that he once had to look at other brands’ gloves instead of a pair from Hermès because they didn’t fit perfectly. Although she already started seeing brands tackling the issue with infrared technology, it hasn’t been widely adopted.

The industry’s inclination for a sense of rarity may also be a potential problem. While brands like Chanel and Celine reportedly need six months or longer to ship a bespoke order, some newcomers in the West, like the leatherwear producer 1Atelier have built their business model on made-to-order, promising to deliver their customized bags (cost between $300 and $8,000) in three weeks. Ermenegildo Zegna is also promising a similar delivery time for their made-to-measure suits and shirts in China, according to its website, but it would still take most other brands more than three months.

Such sentiment is agreed by Demiri. “In China, personalization or customization is not done with a Chinese lens; it’s done with Western lens,” he says. “But I think China is ready, and brands should cater to what the Chinese consumers demand.”

Over the past few years, certain brands might have already learned their lessons from offering made-to-order services in different parts of the world. Now, they could take their past experiences to go further with the help of technology, especially in China’s vast market, where there is a growing demand from high-net-worth-individuals to show their taste and personality.

This article originally appeared in Jing Daily.