Startups use body-scanning analytics to tackle decades-old problem with nonstandard sizes

By Suzanne Kapner, December 16, 2019

Christopher Moore has a doctorate in physics from MIT and has worked on projects ranging from tracking the world’s oil supply to searching for new cancer drugs. His latest gig is turning out to be the hardest: Helping shoppers find their correct clothing size.

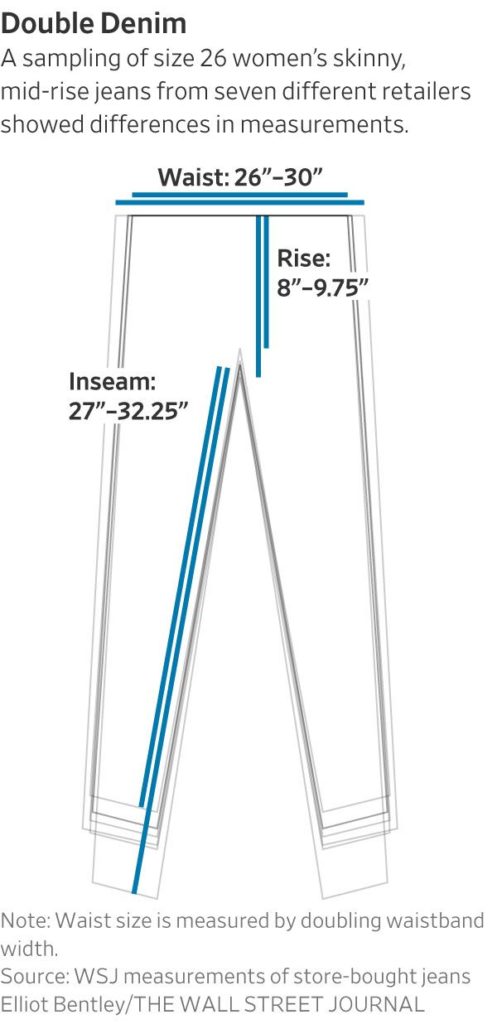

There are no standard clothing sizes, something that anyone who has stood in a dressing room trying on jeans, tops or dresses can attest. As shopping has shifted online, the problem has worsened. Size and fit are among the top reasons for returning online orders, according to e-commerce software company Narvar Inc.—adding an extra layer of costs that further erode retailers’ already thin profit margins.

“Sizing is poorly defined. What do you mean by a size 2?” said Mr. Moore, the chief analytics officer at True Fit Corp., which uses specifications from different brands to help find the right size for consumers who provide their body measurements.

True Fit is among a crop of companies that are trying to solve the fit problem. Others include apps that take 3-D body scans, knitting machines that produce garments with less than 1% variation and custom tailoring services.

None of them provide a perfect solution, according to industry executives. That is because the problem is so complicated, particularly for women’s clothes, which range in sizes from 00 to 18, with plus sizes generally starting at 20. There is no standard that requires an 8 in one brand to fit the same as an 8 in another. Men have it a little easier. Their clothes are based on verifiable chest, waist and inseam measurements.

Ed Gribbin, who developed one of the first body-scanning machines in 2001, said clothes from different brands fit differently on purpose. “The brands use the data to tailor their fit to who they think are their target customers,” said Mr. Gribbin, who is now chief engagement officer of Impactiva, which helps brands and retailers with quality and other production issues.

The largest pair and smallest pair of the same size jeans from two different stores. PHOTO: MICHAEL BUCHER/THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

In September, Human Solutions of North America Inc. mapped the sizes of 18,000 people in the U.S. and Canada, ages 6 to 75, using its 3-D body scanners. The study, which was sponsored by major retailers including Gap Inc. and Target Corp., also asked a series of questions, including how hard it was to find clothes that fit. Seventy percent of respondents said it was very difficult.

A TECH TAILOR?

Retailers and clothing makers have been trying to solve the size problem for decades. Here are some current attempts.

-

My Size: The MySizeID app uses smartphone sensors, not the camera, to take body measurements. It cross references brands’ sizing tables with customer measurements and recommends the correct size.

-

Hemster: Works with retailers including Ted Baker and Diane von Furstenberg. Store workers use a special ruler to mark up garments to customers’ specifications and send them to Hemster for tailoring. Hemster keeps the measurements for future purchases and returns the garments to the store, where shoppers pick them up.

-

True Fit: Helps online shoppers find their correct size at different stores such as Macy’s and J.Crew. It analyzes product specifications and anonymous sales and return data. It pairs that information with body and style preferences from shopper questionnaires.

-

MTailor: Its app takes measurements using a smartphone camera. Users place the phone on the floor against a wall, stand back 6 feet and turn around once. MTailor uses the measurements to create custom suits, shirts, pants and jeans for men.

-

Shima Seiki: This Japanese company makes 3-D knitting machines that produce garments with less than 1% variation in sizing. Garments are produced in one piece without seams and based on body specifications.

The measurements underlying current size charts are so out of date that companies are having trouble finding fit models who meet their specifications, said Andre Luebke, North American general manager for Human Solutions. The biggest change is waist sizes have gotten bigger.

Some large retailers, including Walmart Inc., are taking steps to ensure their clothes fit better. A Walmart spokeswoman said the company was working with industry experts and using technology to better understand and solve issues related to consistency in size and fit.

Inaccurate size tables are only part of the problem. Oftentimes, those tables are generic and don’t reflect the measurements of actual items, said Don Howard, executive director of Alvanon Inc., a consulting firm that helps brands and retailers with size and fit. They also don’t explain how fabrics fit. A stretchy fabric might mean downsizing; a fabric with less give could require sizing up.

Further complicating matters is the diverse body shapes of American consumers. A study in the early 2000s sponsored by clothing retailers and manufacturers called SizeUSA measured more than 10,000 people and found that the hip circumference of women with a 28-inch waist varied from 32 inches to 45 inches.

Brands have tried to solve for this problem by adding new silhouettes such as curvy or straight, sometimes creating even more confusion for consumers.

Madison Price said she has stopped buying clothes online because she is tired of returning items that don’t fit. Yet, the 27-year-old musician doesn’t fare much better when she visits her local stores. On a recent trip to Target, she bought a Wild Fable denim jumpsuit in an extra small, but when she tried on a turtle neck from the same brand in the same size, it was too tight.

“Sometimes, I’ll be an extra small, sometimes I’ll be a medium,” the St. Louis resident said. “The sizing is all over the place.”

A Target spokeswoman said sometimes items are designed to fit differently based on the style, and these details are often included in the item description on its website.

Some executives are predicting that sizes will become obsolete.

“Sizes will go out the window 10 years from now,” Levi Strauss & Co. CEO Chip Bergh said last month. “Everybody will be able to do their own body scan on a camera.”

Body-scanning offers precision, but it can cause a different type of discomfort. A startup called My Size Inc. discovered that shoppers weren’t always happy with the size recommendation when it tested its body-scanning app in a New York pop-up store in July.

“They’d say, ’I’m not a large, I’m a medium,’” said Ronen Luzon, My Size’s chief executive. To get around the problem, MySize ran a second test in which it replaced sizes with colors.

Lined up on one side, the discrepancies in jeans across different brands is clear. PHOTO: MICHAEL BUCHER/THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

Most apparel in preindustrial America was made-to-measure at home or by professional dressmakers and tailors. That changed during the Civil War, when factories churned out military uniforms, according to the National Institute of Standards and Technology.

Women’s ready-to-wear clothing took off in the 1930s, and by the end of that decade the U.S. Department of Agriculture conducted the first large-scale study of women’s body sizes. Technicians took 59 measurements from about 15,000 women. The data were flawed, partly because the study only included white women, said Lynn Boorady, a professor at Oklahoma State University, who has studied the subject.

In the mid-1940s, the Mail Order Association of America, which was grappling with high return rates, urged a predecessor of the Institute to reanalyze the Agriculture Department data. The result became the basis for clothing sizes in 1958.

As Americans got bigger, manufacturers adopted vanity sizing in the 1980s; clothing got larger, but the sizes stayed the same.

The SizeUSA study last decade determined there were more than 300 standard measurements, resulting in thousands of size combinations. Manufacturers didn’t need to make them all, but the data was sent to them raw and decoding it would have required a statistician, Ms. Boorady said.

Some brands are sidestepping the size issue altogether. Instead of small, medium and large, athletic-wear maker Grrrl Clothing names its sizes after female athletes, including Heidi Cordner, a 6-foot arm-wrestling champion, and Zhang Weili, a strawweight champion in the Ultimate Fighting Championship.

Shoppers still have to match their measurements to those posted on the website for each athlete. “But they don’t have to deal with the stigma of ordering a XXL,” Chief Executive Kortney Olson said.

This article originally appeared in The Wall Street Journal.